The Supreme Court of India on December 12, 2024 ruled that no civil court should accept any new pleas challenging the 1991 Places of Worship Act till the next hearing on the matter in the apex court. The court also said that no new orders should be passed in the suits that are already pending before various courts.

Places Of Worship Act: A Test Of India's Secular Soul

What is the Places of Worship Act, and What does the Supreme Court of India have to do with Sambhal and other such cases? Outlook Explains.

The Supreme Court is currently hearing a batch of petitions on the issue and is set to decide on the scope of the Places of Worship Act. In this context, here is an article from the Outlook archives explaining the Places of Worship Act, 1991 in the context of recent surveys ordered in mosques and the trigger points for this in the Ram Janmabhoomi verdict.

On the eve of the Constitution Day, November 25, 2024, the Supreme Court of India dismissed petitions seeking to exclude the terms "socialist" and "secular" in the Preamble of the Indian Constitution. In a succinct seven-page order, the court remarked that, "Over time," India has developed its own interpretation of secularism, wherein the State neither supports any religion nor penalises the profession and practice of any faith. This principle is enshrined in Articles 14, 15, and 16 of the Constitution,” the apex court said.

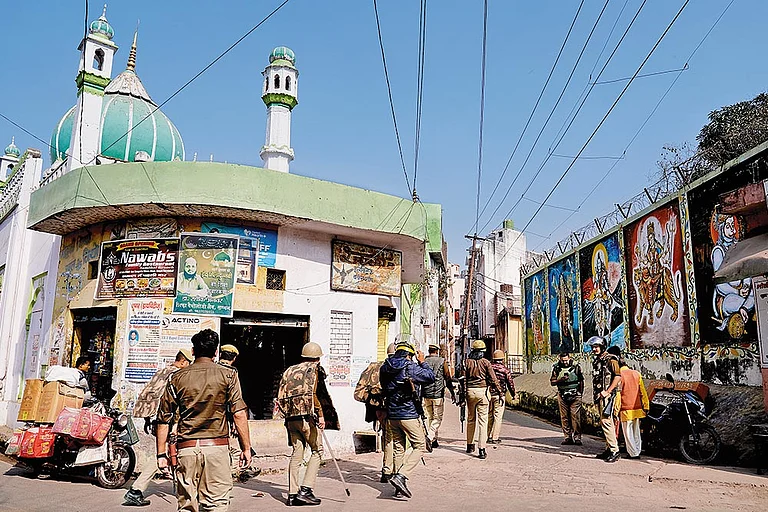

Some 160 kilometres away, violence between Muslim residents and local police over fears of a mosque's demolition led to an unrest that left many dead. The incident started with a lower court's order to survey the religious structure to investigate claims that it had been built on the ruins of a Hindu temple 500 years ago.

These twin events—one a judicial affirmation of constitutional ideals, the other a harrowing episode of communal discord—unfolded simultaneously. They also raised urgent questions about the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act of 199, legislation meant to protect modern India’s secular fabric from historical grudges.

Enacted a year after the violent clashes over the Babri Masjid during the peak of the Ram Mandir movement, the Places of Worship Act froze the religious character of places of worship to their standing at on August 15, 1947. The law aimed to prevent future conflicts and uphold communal harmony.

Introducing the legislation in Parliament, then-Home Minister S.B. Chavan had declared that the law’s purpose was to ensure that "old controversies which had long been forgotten by the people" were not revived to disrupt social peace.

The Act’s Section 3 barred the conversion of any place of worship, while the preamble underscored the importance of maintaining the "religious character" of such sites. Notably, the law excluded the Babri Masjid–Ram Janmabhoomi dispute from its purview, recognising the uniquely volatile nature of that case.

In its landmark 2019 Ayodhya judgment, the Supreme Court reaffirmed the Act’s constitutional import, calling it as a “bulwark against communal retrogression.” The court explicitly rejected the notion of using contemporary legal mechanisms to rectify historical wrongs, stating, “Our history is replete with actions that have been judged to be morally incorrect.” The judgment underscored that reopening such wounds would undermine the very secular principles the Constitution sought to uphold.

The Supreme Court has been accused of undermining the Act’s spirit by allowing surveys and legal proceedings in cases like the Gyanvapi Mosque in Kashi and the Idgah Mosque in Mathura.

In these cases, lower courts have permitted inquiries into the “religious character” of these sites, often citing the Act’s supposed ambiguity about the term. This interpretation stands in stark contrast to the Ayodhya judgment, where the court had cautioned against using the law as a tool to settle ancient disputes.

The Gyanvapi case is emblematic of this trend. While the mosque committee argued that the Act barred such proceedings, the courts allowed the case to proceed, reasoning that determining the “original” character of the site did not constitute a conversion. Such rulings have emboldened litigants across the country to challenge the religious status of various sites, threatening to unravel the very fabric of communal harmony that the Act was designed to protect.

While the judiciary has repeatedly upheld the constitutional principle of secularism in theory, its actions in cases like Gyanvapi and Mathura have emboldened those seeking to weaponise history for political and communal gains.

The Places of Worship Act, despite its flaws, remains a crucial safeguard against the exploitation of religious sentiments. By freezing the status of places of worship as they stood at independence, it acknowledges the complexities of India’s history while prioritising the need for harmony in the present.

Yet, the judiciary’s recent actions threaten to dilute this safeguard. By permitting surveys and inquiries that effectively challenge the Act’s intent, the courts have opened a Pandora’s box of communal disputes, endangering the fragile peace that the law sought to preserve.

The tragic events in Sambhal serve as a stark reminder of the consequences of failing to uphold these principles. They underscore the importance of viewing places of worship not as symbols of division but as spaces for unity and coexistence.

In the words of the Supreme Court’s November 25 order, “India has developed its own interpretation of secularism.” Whether that interpretation will remains to be seen.

-

Previous Story

Places Of Worship Act: Supreme Court Hearing, The Controversy And More | Explained

Places Of Worship Act: Supreme Court Hearing, The Controversy And More | Explained - Next Story