Climate change will likely make the Delhi-Mumbai comparison moot because one will burn and the other will drown. For millions of working people in these two cities, the treadmill of making ends meet, making rent and making it to work on time, makes competing claims to cosmopolitanism feel like nakhra, the narcissism of an English-speaking middle class with time to spare and points to score.

Lutyens’ Delhi: Alienating Itself From The Past

Mumbai is all of a piece in its colonial and postcolonial modernity, whereas Delhi’s modernity, such as it is, is at odds with its medieval past

For anglophone Mumbaikars, their city is the nearest thing India has to the western metropolis: nearly London, almost New York, Urbs Prima in Indis with Bollywood bolted on. In this telling, Nariman Point is Wall Street and Bandra West is Brooklyn and the Gateway announces India in the way that Lady Liberty embodies the United States.

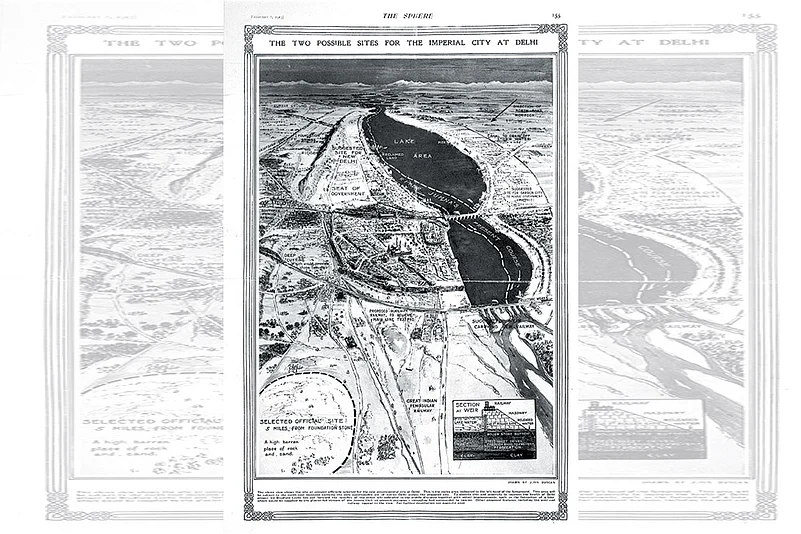

For their countrified cousins in Delhi, the capital’s hybrid achievement is to have grafted a Western capitol on to the ruins of several old, superseded cities; think Washington D.C. or Canberra, with History en suite.

I grew up in Lutyens’s Delhi in the government housing supplied by the state to its employees. These were whitewashed homes of various sizes classified by letters and assigned by rank. So if you lived in A/B type houses, it meant your father (more rarely your mother) was at least an additional secretary, whereas C-I or C-II homes housed more middling joint secretaries. Our semi-detached house along with its neighbours looked on to a reasonably level, hedged-in green that was made for playing cricket.

This wasn’t cricket as played in a public maidan (ground) like Shivaji Park. New Delhi in the 1960s wasn’t a high-density metropolis where public parks were shared out in a dozen cricket matches. It was a babu pastoral where space was no consideration, and sarkari children had the run of the greens that their ‘colonies’ enclosed.

The capitol that Edwin Lutyens built accounts for less than five per cent of contemporary Delhi’s area and is wholly unrepresentative of its current density, but it influenced the way in which the republican capital expanded. For nearly 40 years, Delhi’s planners and builders played variations on the park-and-bungalow theme, producing progressively meaner neighbourhoods and rampant urban sprawl. It wasn’t till the late 1980s that the idea of the purpose-built apartment building took root in Delhi, which is why tall apartment blocks are largely confined to the outer reaches of the National Capital Region, principally in the satellite townships of NOIDA and Gurugram.

For anglophone Mumbaikars, their city is the nearest thing India has to the western metropolis: nearly London, almost New York, urbs prima in Indis with Bollywood bolted on.

If there is one thing that sets Delhi apart from Mumbai, it’s the curious idea that every home and every institutional building needs to be cordoned off from the street by a little lawn or apron of area, a campus of some sort. The mixed-use city block that rises off the pavement and defines Mumbai’s streetscape was never the norm in Delhi.

The rhetorical disparagement of Delhi as a city of rustic junglees misses the point. Delhi did enfold villages into itself as it expanded; the dense, relatively unregulated lal dora enclaves that dot the city testify to this incorporation. But outside of the walled city of Shahjahanabad, Delhi is less a collection of villages than a cluster of suburbs. The dream of suburban living that gave us modern Delhi is still discernible in the garages now turned into servant quarters, the servant quarters tarted up into tiny apartments, the ground floor gardens cemented into parking lots and the boundary walls replaced by continuous gates that allow for easy parking.

The yearning for the kothi lifestyle haunts Delhi even as property values turn those single-family homes into steepling apartment buildings that tower over tiny colonies not designed to contain them. This suburban aspiration is why Delhi is so hostile to pedestrians and commuters; its neighbourhoods were designed for motorised householders, driving and riding their cars and scooters into the city, then back again.

Till the coming of the Metro, Delhi was the worst-served large city in the world in the matter of public transportation. Having long ago abandoned trams, Delhi never seriously invested in commuter trains, unlike Mumbai, and its bus service was a dangerous, overcrowded joke played on its straitened, long-suffering citizens. The first time I went to Mumbai as a 12-year-old, I was amazed when I saw people queue at a bus stop and then unbelieving when the double-decker’s conductor turned passengers away because he had decided the bus was full up. The Delhi Metro is potentially the most democratic development in the recent history of the city, but it’s too expensive for its poorest citizens. Having exiled the working poor who service the city to slummy Jhuggi Jhopadi colonies, Delhi’s rulers see no reason to make their daily commute more affordable.

In The Idea of India, Sunil Khilnani has a fine chapter on India’s cities where he divides them into two sorts: the great port cities founded in the 17th century that were wholly creatures of colonialism and the pre-colonial cities that were remodelled by the colonial state in the mid-19th and early 20th centuries for the military security of the Raj and its greater glory. This is the basic difference between Mumbai and Delhi: Mumbai is all of a piece in its colonial and postcolonial modernity, whereas Delhi’s modernity, such as it is, is at odds with its medieval past.

I used to think that the idea of colonialism creating a historical rupture was romantic and overstated till I visited Istanbul. Istanbul isn’t just old; its extant heritage buildings are so magnificent and well-preserved that they make Delhi with its vaunted past seem like a provincial upstart. But it was the city’s Ottoman monuments built after the Turkish conquest of Constantinople in the mid-15th century that got me thinking about how similar and yet how different Istanbul was from my city.

The Blue Mosque and the mausoleum of Sultan Ahmet were built less than 40 years before Shah Jahan built the Jama Masjid and the walled city around it. Sultan Ahmet was, if you like, the Turkish Shah Jahan. And yet, as I walked around his monuments, they felt oddly contemporary because they were furnished. There were carpets on the floor, and curtains, clocks and vacuum cleaners. Ahmet’s tomb had wooden cases filled with things he used, like books, swords and relics of the Prophet. Even the graves seemed lived in, covered as they were with tented rugs, almost as if there was someone home.

Delhi’s great monuments, even those in continuous use like the Jama Masjid, are bare. This is partly because they were built for a different climate. Istanbul is the same latitude as New York and therefore colder. Unlike the Jama Masjid’s great courtyard, open to the sky, the Blue Mosque’s congregations gather in a great domed hall. But the other reason Delhi’s medieval monuments are bare and unfurnished is because the world that made them didn’t survive into the present. The interior of Humayun’s Tomb used to be draped and carpeted and lit once upon a time, because it was tended by his descendants.

For nearly 40 years, Delhi’s planners played variations on the park-and-bungalow theme, producing progressively meaner neighbourhoods and rampant urban sprawl.

Inside the Blue Mosque, the time inside the monument and the time outside it, seem in sync. The bareness of Delhi’s medieval monuments, the lack of anything perishable that might need tending, make them seem infinitely older than the world outside. They feel like imposing shells that have been waiting for centuries for someone to furnish them. The reason for this difference isn’t hard to find. Colonialism was an existential displacement; the change of ownership it implied sterilised the monuments that the colonial state took into its care. When things stop belonging to the worlds that made them, they become relics. Khilnani describes this perfectly: “The superb ruins, tombs and monuments of Delhi…were pinioned by Lutyens’s axial layout and turned into follies on the imperial estate: they served as mere ornaments to the viceregal omphalos.”

There is something feverish about the way in which Dilliwallahs alienate themselves from their past. It’s evident in the way in which the upwardly mobile middle class abandoned the old city first for Lutyens’s new capital and then for the suburban pleasures of South Delhi’s gated neighbourhoods. As this class moved south, it traded in the schools it used to send its children to, for new ones. When I was in school, everyone I knew went to St. Xavier’s, St. Columba’s, Mater Dei Convent, the Convent of Jesus and Mary, Presentation Convent, Modern School, Delhi Public School and Springdales. Then, suddenly, these places became less desirable as people moved on to schools further south: Sardar Patel Vidyalaya, Shri Ram School and Vasant Valley School, and now the schools du jour are the expensive ‘international’ schools that prep schoolchildren for their NRI futures. That new schools emerged as the city grew is understandable. It’s less clear why the earlier schools, so sought after once, were abandoned entirely by the class that once thronged them.

This footloose class, so willing to up stakes and move to the next new thing, is now on the verge of abandoning the city altogether. Over the last 30 years, Delhi has looked on as a large chunk of its aspirational middle class has transplanted itself to Gurugram. It has followed the large companies and corporations that found the commercial and office spaces in Gurugram that Delhi lacked. The extraordinary thing about this great migration is that Delhi’s rulers—its municipalities, its state government—have looked on as Delhi’s tax base—the companies and high net worth individuals that swell a city’s revenues—migrated to a neighbouring city. Once that happens, the rest—clubs, golf courses, shops, schools, museums and culture in general—inexorably follow. It’s hard to imagine Mumbai allowing this to happen without a fight. Delhi rulers are so consumed by politics, by the practice of power for its own sake, that they are fundamentally unserious about the economic realities that undergird great cities.

One of the things that makes a metropolis ‘great’ is the way it lives in the minds of outsiders. New York, Istanbul, Sydney, London and Paris are storied places; they live in novels, songs, photographs, films and commercials. When I visited New York for the first time at the age of 30, I was assailed by secondhand shocks of recognition. I hadn’t been to Central Park before, but I had seen it in the movies. It’s that faux sense of déjà vu that makes cities and their landmarks ‘iconic’. Ironically, despite its instantly recognisable monuments and its political pre-eminence, Delhi can’t begin to compete with Mumbai in this race. A century of cinema has made sure that the city is etched in the minds of everyone who has ever watched a Hindi film.

It’s not that Delhi’s locations and landmarks aren’t captured in fiction and film; they are. I think of Delhi Belly and its grossly funny evocation of young men about town, and Paatal Lok with its deadpan retelling of violence in Delhi’s remote badlands, its Outer Jamuna Paar, and I know that outsiders who come to Delhi having seen those films will feel the same shock of recognition that I felt when I first visited Mumbai or New York. The nice irony of this is that these stories of Delhi will have been told by Mumbai.

(Views expressed are personal)

- Previous Story

Parliament Session: VP Dhankar Accused Of Silencing Opposition; Rahul Gandhi Meets With Lok Sabha Speaker | Latest

Parliament Session: VP Dhankar Accused Of Silencing Opposition; Rahul Gandhi Meets With Lok Sabha Speaker | Latest - Next Story