“You probably doubt that we were capable of joy,

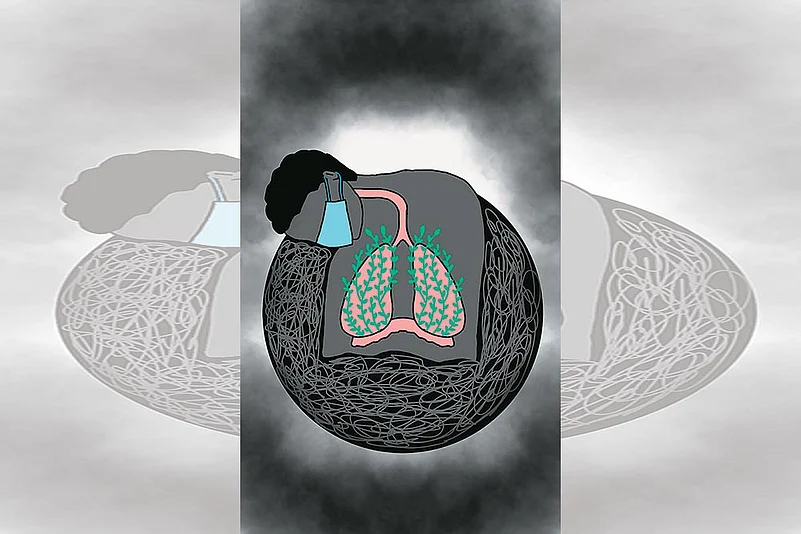

Can India Have A Pollution-Free Future?

Even as the country faces existential threats, there may be hope ahead

but I assure you we were.

We still had the night sky back then,

and like our ancestors, we admired

its illuminated doodles…

Absolutely, there were some forests left!

Absolutely, we still had some lakes!

I’m saying, it wasn’t all lead paint and sulfur dioxide”

—Letter to Someone Living Fifty Years from Now, Matthew Olzmann

Seven years ago, a family of three moved to Delhi with two bags in hand, and big dreams in their hearts. Rajesh, who belongs to Bharatpur, Rajasthan, found a job as a cab driver in the capital. His wife Jyoti enrolled their six-year-old son, Anurag, in school. Anurag made new friends. Jyoti joined a women’s self-help group in their neighbourhood. The three of them got used to Delhi’s rhythm, but what they couldn’t handle was the pollution. Anurag developed a chronic cough and breathing problems. Hospital visits became a regular nightmare. Rajesh also had his share of health troubles: chest pain crippled him when the air quality worsened in winter. His eyes would water all the time and customers would ask him why he looked so sad when he ferried them across town. He carried on working, but he couldn’t bear to see his son suffer. In two years, an anxious Rajesh convinced Jyoti and Anurag to move back to their hometown. He promised to visit them every month.

Rajesh and his family are among many whose lives have been disrupted by Delhi’s pollution menace. In “pollution season” (October to December), when the air quality plummets the most, the number of patients at city hospitals with breathlessness and other respiratory problems increases sharply. A survey by LocalCircles, a Delhi-based platform, found that 80 per cent of families in the city have at least one member who suffers from pollution-related health issues. Forty-eight per cent of them are affected by air pollution. In the 2023 IQAir air quality global ranking of cities, Delhi is listed as the most polluted capital in the world. Nine of the top ten most polluted cities on the list are in India and 83 Indian cities figure among the 100 most polluted cities globally.

It isn’t just the air we breathe. Water, the vital life force, is under threat too. Six per cent of the Indian population lacks access to safe water according to a Water.org report. Drinking water sources are polluted in many parts of the country. According to Satish Sinha, Associate Director, Toxics Link, there is “growing evidence of increased contamination of surface water with microplastics. We [India] are yet to set standards for microplastics in drinking water.”

Every Breath You Take

Air pollution is often labelled a “silent killer”. But considering the damage it inflicts on lives and livelihoods, it’s more apt to call it an aggressive assassin. A study by researchers at Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University found that pollution caused by man-made emissions and disasters like wildfires can be linked to 135 million premature deaths worldwide between 1980-2020. Extreme weather events caused by climate change intensify the concentration of pollutants in the air.

A multi-city study in India, published in the Lancet, has found that over 33,000 deaths in the country annually can be attributed to short-term exposure to air pollution. These are caused by inhaling ultra-fine particulate matter (PM 2.5) at levels that are much higher than the 24-hour limit set by the World Health Organization (WHO). The WHO classifies PM 2.5 above 5 mg per cubic metre as unsafe while Indian air quality norms allow annual average PM 2.5 concentrations of up to 40 mg per cubic metre.

A multi-city study in India, published in the Lancet, found that over 33,000 deaths in the country annually can be attributed to short-term exposure to air pollution.

According to ‘State of Global Air (SoGa) 2024’ published by the Health Effects Institute, 464 children under the age of five die in India daily due to factors associated with air pollution. Children’s lungs are still developing. This makes their vulnerable bodies much more susceptible to the dangers of breathing in particulate matter. The particles are so fine that once inhaled, they can penetrate the lungs, enter the blood stream, and cause damage to all organs. Inhaling PM 2.5 poses serious health risks to both children and adults. In children, it can cause asthma, reduction in brain volume, behavioural dysfunction, and impaired lung growth. Another alarming affect: PM 2.5 pollution decreases children’s Performance IQ (PIQ), the type of intelligence which makes them good at adapting to change and solving problems. The damage caused in childhood can have a long-lasting impact on their lives.

According to Ghodajkar Prachinkumar Rajeshrao, Assistant Professor, Centre of Social Medicine and Community Health, Jawaharlal Nehru University, air pollution is an “equaliser” since it affects people from all classes. “But those who lack access to clean water and safe housing are disproportionately affected,” he says. “Comprehensive solutions for the problem have to bring all social groups to a common platform.”

Troubled Waters

In 2024, pollutants contaminating groundwater are reported to have affected over two million Indians. Water quality deteriorates due to dumping of industrial waste, domestic sewage, and agricultural runoff in rivers and lakes. Only 28 per cent of urban sewage is treated before being disposed off in lakes, rivers, and aquifers. Rivers such as the Yamuna and the Ganga, which are considered sacred and worshipped by many, are clogged with untreated waste and disposed idols and flowers.

Uncontaminated freshwater sources are dwindling. The scarcity of safe water has set off a wave of migration to cities from rural areas. “Access to clean drinking water is still a distant dream for people living in various parts of our country,” says Sinha. “Different geographies have different challenges and we have not addressed them all,” he adds, while pointing out that government schemes like ‘Nal Jal Yojana’ are appreciable, but a lot more needs to be done by both the Central and the state governments.

Salvaging the Future

Amidst the gloom, are there glimmers of light? Can we work for a pollution-free future even as we face existential threats? Hope is always at hand. And as Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg said, “Hope is not passive…Hope is taking action.” An actionable, much-needed step in the right direction would be the revision of India’s current air quality standards, which are much more lenient than WHO limits. In a recent interaction with a news agency, environmentalist Sunita Narain, Director General of Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), called for “steps to be taken at the speed at which the crisis is happening”.

With a groundwater shortage accelerated by climate change looming, water is fast becoming a scarce resource. Conservation efforts and the monitoring of the quality of water bodies must be stepped up. Upgradation of waste water treatment plants is also crucial. Many citizen-led groups are spearheading the cleanup of polluted rivers and lakes. Individuals and civil society groups have approached the courts to safeguard rivers from pollution any number of times.

With the Indian Supreme Court recognising the right against climate change to protect the fundamental rights to life and to a clean environment, policymakers will have to tackle pollution and climate change jointly to find effective solutions. India has overtaken China to become the single most populous country in the world. In light of this fact, the need for humane, environmentally sound policies that protect Indians from pollution becomes all the more urgent.

(This appeared in print as 'Elemental Emergency')

- Previous Story

Elections 2024: Ashok Tanwar Joins Congress Again; Sehwag Endorses Congress Candidate In Haryana

Elections 2024: Ashok Tanwar Joins Congress Again; Sehwag Endorses Congress Candidate In Haryana - Next Story