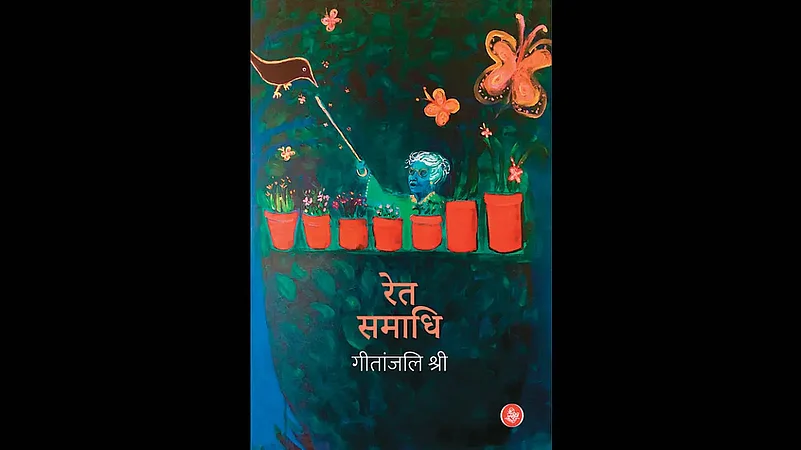

Geetanjali Shree’s Hindi novel Ret Samadhi, translated into English by Daisy Rockwell as Tomb of Sand (Penguin Random House), has made it to the shortlist of six at the 2022 International Booker Prize, where it will stay in hopeful suspense until the winner is announced on May 26. This comes as a pleasant surprise and calls for celebration not only in the Hindi world, but well beyond it.

Beyond The Borders: When A Hindi Novel Gets Shortlisted For Booker

A language that struggles to get recognition in its native land is now one step away from a major international award. Will it pave the way for more Hindi novelists to overcome different boundaries?

Soon after Tomb of Sand got longlisted, its Hindi publisher organised a reception in New Delhi. The announcement report published in The Guardian led off with the mention of Tomb of Sand, which the jury chair said was the first Hindi novel to be ever nominated for the prize. Moreover, the article only carried Shree’s photograph. The highlight of the longlist this year was that it included a novel in a language as remote as Hindi (globally), even though author Olga Tokarczuk too figured on the list for her Polish novel, The Books of Jacob. Tokarczuk had received this award for her novel Flights in 2018, the same year she received the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Tomb of Sand is not only the first Hindi novel, it is also the first novel from any Indian language to be nominated for the International Booker Prize (IBP), launched in 2005 to supplement the main Booker Prize, running since 1969 and strictly for novelists writing in English. IBP carries the same prize amount (GBP 50,000) but is divided equally between the author and the translator. The prize belatedly acknowledges the obvious, but often overlooked fact that not everyone in the world writes in English.

Till 2016, IBP was not an award for a book, but a lifetime achievement award given once in two years for a body of work in English or its English translation. In 2013, U.R. Anan-t-h-amurthy (Kannada) and Intizar Husain (Urdu) were shortlisted for the prize. From 2016, the award became an annual endeavour, given to a book translated into English. This development brought it on a par with what many Western readers may view as the real Booker, with one book winning the award each year in both categories.

Not many of us had heard of the original Booker till our man Salman Rushdie won it in 1981, and many of us in India had probably not heard of IBP till a month ago. The prize has brought on enhanced fame for Geetanjali Shree, and she in turn helped the prize become known in India. In other words, the validation is mutual.

Published in Hindi in 2018, Ret Samadhi had not been waiting for a princely foreign award to come and wake it up with a kiss. It was brought out by Rajkamal Prakashan—India’s biggest publishing house for Hindi literature—whose owner Ashok Maheshwari immediately sensed its worth. He promptly hosted an evening of discussion and celebration centred on this one book—an honour accorded only to a small fraction of the hundreds of books he publishes every year. Then, in January 2019, the novel got a whole slot for itself at the Jaipur Literature Festival (JLF).

As her interlocutor at that JLF session, conducted in Hindi, I had the pleasure of hailing her book as the kind that comes along just once or twice in a decade and buttonholes us with its originality of theme and novelty of style. Listing the major virtues of her novel, I pointed to its sensitive treatment of the aged and the transgenders that are two neglected segments of society, the gobsmacking tran-si-t-ion of location in the book’s last section, and the sheer variety and virtuosity of language that is not content with merely narrating, but constantly performs little tricks of its own.

In a recent interview, Shree declined to comment on what her next novel was going to be about, and called such labelling reductive. But most readers persist with this question, prioritising thematic concerns over finer artistic nuances. The novel begins: “This story will tell itself” (or, in Rockwell’s translation, “A tale tells itself”), but it will surely not suffice to say, solipsistically.

In a nutshell, this novel is about conte-mp-o-rary Indian households of the educated, affluent class having to cope with an aging parent, and with each other in terms of resenting how little the other does when it comes to shared responsibilities. It is about loneliness and helplessness of old age, further complicated by forgetfulness and waywardness. It is also about noticing that our world is surrounded by and intermeshed with non-human life forms; represented by ever-cawing crows in the book. Further, it is about mutual incomprehension and resultant hostility created by any form of political and social division.

Several reviews of the book and interviews with the author in Hindi periodicals have come out. In a recent interview, Shree was asked to survey her whole career, since her childhood through her four previous novels. She may not have exactly set the Yamuna on fire, but she has not languished unsung in Hindi either for the lack of attention from London. After the longlist announcement, there was a perceptible wave of excitement and renewed interest in the novel in Hindi. According to trade reports, the Hindi edition is selling far better than its English translation. However, the Hindi version had good sales even before the English translation came out. In a rare phenomenon, the tail of translation seems to be wagging the dog of the original.

The reaction to the news of the Booker short-list in the Hindi world is as varied as could be expected. Seasoned and well-published writers have said that while the shortlisting is notable for the Hindi language and its market, it has no intrinsic literary significance. On the other hand, a noted writer bemoaned that the novel’s French translation was shortlisted for a prize in France and now its English translation has been shortlisted for the Booker, but it has not received any award in Hindi, and that Shree is yet to be selected for the coveted Sahitya Aka-demi Award. Another Hindi writer and Hindi-to-English translator found the English translation more enjoyable as it seems to have been thought out in English in the first place. The varied responses reflect a gamut of attitudes, from ingrained colonial hostility to English to its postcolonial acceptance and deference to it.

All books change in translation. Even the ones that are not as ceaselessly inventive in conception or compulsively playful in their use of language like Shree’s novel. Its hybrid deployment, in turn, of half-rhyming poetic prose, sharp punning wit, rural-dialect Hindi, occasional English and Sanskrit phrases, and fairly chaste Urdu, particularly in the section set in Pakistan, will challenge any translator. All of this was a bit toned down in a rendering into staid standard English in Rockwell’s tran-slation. It can be said that the English translation exercises a moderating effect on the novel, and brings Shree’s perfervid creativity closer to ‘normal’ room temperature.

Rockwell writes that she had left many Hindi words untranslated, and those who feel the book is “not translated enough into English” should know that “the original was similarly packed with English”. She also claims that “the original novel is artificially Hindi-centric,” implying the book was already half-embedded in English and crying out to be translated. This seems to indicate easy traffic between a kind of Hindi writing now and its English translation, which makes it possible for one to feed off the other, not only in terms of interlinguistic textual composition, but also reputation and circulation.

For all this hybrid mutuality, the breezy English translation in the first place seems to get wrong the title of the Hindi novel, Ret Samadhi, which it renders as Tomb of Sand. The Hindi novel contains an extended passage that shows the Buddha meditating on the sands of the river at Gaya in a ret samadhi, and moving on to meditate in the river in a jal samadhi. In fact, the 2019 JLF session on this novel was titled ‘Meditations on Sand’. But the French translation goes even further. Its title, Au-delà de la frontière, means ‘On the Other Side of the Border’; the translator’s own invention and imposition.

In one sense, the French title is closer to the theme of Shree’s novel than the Hindi title. In the first part of the novel, an old woman is cajoled back from depression to re-engage with life. In the second part, she forms a close friendship with a transgender, and in the third part, crosses over to Pakistan without a visa in search of a long-lost (and presumably long-forgotten) husband. As the Hindi blurb says, the novel is about crossing all kinds of borders “between man and woman, youth and age, mind and body, love and hate, waking and sleeping, joint and nuclear family, India and Pakistan, and humans and other creatures.”

‘Border-crossing’ as a theme is perhaps more relevant in the West at present than in India. Even Tokarczuk, shortlisted with Shree, had won the Nobel Prize for what the citation called ‘her narrative imagination that with encyclopaedic passion represents the crossing of boundaries as a form of life’. However, the most spectacular border-crossing that this novel has accomplished is its own journey from Hindi to English, which has brought it to IBP’s doorstep. It remains to be seen whether the success it has already achieved will have a Rushdie-sque effect—lead more Hindi novelists to cross more borders of one kind or another. Will it also lead to a spurt in translations of Indian novels brought out by British publishers, given that the gate-keeping precondition for the IBP nomination is mandatory publication in the UK?

Meanwhile, let us wish Shree well as she stands waiting to cross the last frontier for the prize. Who says a lot is lost in translation?

(Views expressed are personal)

Harish Trivedi emeritus professor at Delhi University