This story was published as part of Outlook Magazine's 'Future Tense' issue, dated October 11, 2024. To read more stories from the Issue, click here .

The Shifting Nature of 'Delhi's Agents' In Kashmir

Words such as Agent/Agency/Proxy/B-team are dominating the whispers in Kashmir Valley these days as people anxiously wait for the election results on October 8

This town is full of shadows—wrote Kashmir’s celebrated short-story writer Amin Kamil in ‘The Shadow and the Substance’. He talked about the mushrooming of government informers and spies in the Valley for surveillance. In the story, Manohar—the protagonist—is spying on the people for the State but ultimately realises that even he is not immune to surveillance. The story is based on the premise of distrust.

There is a lot of distrust in the Valley these days. It’s election time after 10 years. There are whispers of all kinds. Terms like “Dilli ka agent”, “narrative”, “agency” and "proxy” are frequently used in conversations.

A scene from the bustling markets of Srinagar’s Lal Chowk on a September evening reminds one of Kamil’s shadows.

It’s 4 pm. Shopkeepers are busy selling shawls, carpets and pheran fabric; tourists and locals are trying their best to bargain. Somewhere in the distance, a rally is passing by—loud music is playing; slogans can be heard. At a carpet shop, the conversation shifts to the elections.

One man declares: “The NC (National Conference) will form an alliance with the BJP (Bharatiya Janata Party) if it gets a good number of seats in Kashmir.” The other replies: “No way. It is the only party that can stand up to the BJP.” The discussion goes on for some time.

These days, people in the Valley have a lot of questions, primarily stemming from distrust. Which party is clandestinely serving the Centre’s interest in the Valley? Who is Delhi’s agent and who is not? What are the regional parties—known as Unionists—up to? Why should they be trusted when they are accusing each other of being Delhi’s eyes and ears? What is the narrative that is being built in this election? What will happen after the elections? There are no answers.

The Valley is anxious. Ten years is a long time in politics. A lot has changed in the political landscape of Kashmir between 2014—when the last elections were held—and now.

Political parties tried their best to win the people over during campaigning. Each party tried to convince them that it is not on the same page with Delhi. Leaders of all regional parties promised restoration of Articles 370 and 35A—a closed chapter for the Centre. While development and local issues also found a mention in manifestos, they were almost never heard in political speeches and rallies.

The people are on a different tangent. On the streets of Kashmir, there’s no endorsement of the BJP’s Naya Kashmir narrative. There is, however, a desire to break free from New Delhi's direct rule through an unelected Lieutenant Governor. The people feel government policies have choked spaces for all forms of legitimate dissent. So, in an altered landscape, the vote is their weapon now, they say.

Perceptions have changed. Parties once seen as New Delhi's stooges are now viewed as potential voices of resilience. Khaled, a 23-year-old student, explains: “In Kashmir, mainstream politics has always been aligned with Delhi, while separatists represented the people’s sentiment. With separatists now behind bars, we’re looking at the mainstream to represent our aspirations.” He feels that jobs and development can wait; Kashmiris need to safeguard their identity first.

Agent/Agency/Proxy/B-team

In the political arena, however, it’s the usual case of mudslinging—issues of the people and their interests have taken a backseat. The most talked about person this election season has been Engineer Rashid—the president of the Awami Ittehad Party (AIP). His win in Baramulla in the 2024 Lok Sabha elections, while in Tihar jail, against NC’s Omar Abdullah, indicated a shift in voter sentiment. However, the people soon started wondering, “Who is he to the BJP?” when he was granted interim bail until October 2 to campaign for the Assembly elections.

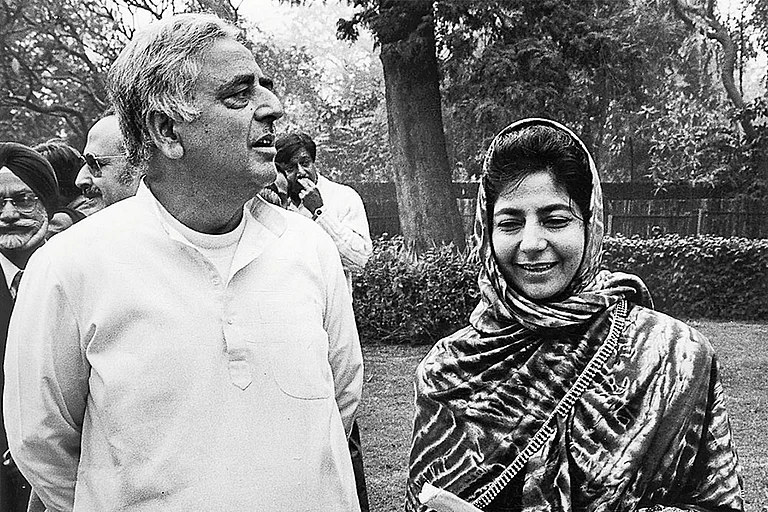

His political opponents—Abdullah and the Peoples Democratic Party’s (PDP) Mehbooba Mufti, both former chief ministers—called him a BJP “proxy” and an “agent” who was bailed out to “divide their votes.” The term “proxy” is used a lot in the Valley these days for a political party suspected of having or eyeing a tie-up with the BJP to form the government. An “agent”, meanwhile, could be an Indian agent or Pakistani.

The Baramulla MP, in his first interaction with journalists on September 11 after his release from Tihar jail, shot down the NC and PDP charges. “How can a man who has been a victim of the BJP’s politics be its proxy? I will fight against Modi's ideology till my last breath,” he said.

When Rashid fielded candidates from the PDP’s bastion in South Kashmir’s Shopian, Mufti took a dig at him. She alleged that Rashid’s party was being aided by government agencies. “Who finds candidates for the AIP when Engineer Rashid is in prison? From where do these caravans of cars come? Who supplies money? Shak to hota hai (it sounds doubtful),” she said in an interview.

On September 12, in North Kashmir’s Kupwara, NC vice president Abdullah criticised the BJP for overtly trying to divide votes in the Valley by supporting its ‘proxies’. “Do not let the BJP’s tactics succeed,” he asserted. “If anyone wants a BJP-led government in J&K, they should support the AIP, PC (People’s Conference), and Apni Party (AP).

The narrative manufactured by the NC and the PDP is that Sajad Lone led-PC, AP and AIP are representing the BJP in the Valley. Their party symbols—Apple, BAT and Pressure Cooker, respectively—are perceived as vote disruptors.

Before the elections, some faces were famously “seen” as pro-BJP, but even they changed the narrative while campaigning, confusing voters even more. Among them is PC chief Lone— locally known as the “BJP’s poster boy”. He surprised all when he raised anti-Modi and anti-BJP slogans—‘Modi ka jo yaar hai, gaddar hai gaddar hai’ and ‘BJP ka jo yaar hai, gaddar hai gaddar hai’—after filing his nomination for the Kupwara assembly segment. He said those hand-in-glove with the BJP were labelling him pro-BJP, referring to Abdullah who served as the junior minister, MEA in the BJP-led NDA government in early 2000. Lone seems to have understood that this is the only narrative that works in Kashmir and results in an electoral dividend.

However, the people have not forgotten that Lone, too, was a cabinet member in the PDP-BJP government, from the BJP’s quota, which collapsed in 2018. Moreover, after meeting PM Modi at his official residence in 2014, Lone referred to him as his “elder brother”.

A political scientist based in Kashmir believes over time, there has been an assault on Kashmir’s position and identity—the scrapping of constitutional posts such as Wazir e Azam (Prime Minister) and Sadr e Riyasat (President) in the 1960s, the systematic erasure of J&K’s separate Constitution and separate flag and the gradual hollowing of Article 370 over decades, among others. Large sections of the people hold the Congress and the BJP governments in New Delhi responsible for their collective disempowerment while employing tools of democracy. That’s why the mainstream parties traditionally viewed as pro-Delhi often portray themselves as victims of Delhi during election time, he explains.

All these factors have managed to confuse the voters. While the core supporters of each party believe that their respective leaders are the only ones who summon the courage to challenge New Delhi, for others, things stay unclear and vague.

Salim, 21, an NC supporter, believes that his party’s pre-poll alliance with the Congress proves it won't ally with the BJP, while Mudassir, 35, who supports the AIP, thinks the party deserves a chance to prove its loyalty, arguing that others have had their chances. “It’s about time for a new player to emerge,” he says.

Abdul Gaffar, 56, a former PDP voter, has lost trust in politicians after the party’s 2014 alliance with the BJP. “Politicians eat promises with bread here. Any of them can form an alliance with the BJP, presenting any argument in any situation as they deem necessary,” he says.

Not The First Time

This is not the first instance of the anti-Delhi narrative being used to generate public support on Kashmir's turf. It goes back to 1953 when Mirza Afzal Beg—the confidante of NC’s Sheikh Abdullah—led the Plebiscite Front, a people's movement for a referendum, duly endorsed by Abdullah from prison.

As the movement gained traction, many people were killed, thousands arrested, and families destroyed. Sheikh would refer to his rivals as “Congressmen or agents and pawns of Delhi” because during his political stint, the Congress was to that generation of Kashmir what the BJP is today to the current.

The plebiscite movement lasted for 22 long years until it was disbanded in 1975 to pave the way for Sheikh’s return to power. He returned as chief minister, not as Prime Minister, and defended his U-turn as a ‘change in the strategy while the goal remained the same’. Critics accused Sheikh of betraying the people’s trust, claiming that his plebiscite demand was just a political tactic to gain power.

Similarly, since its creation in 1999, the PDP has advocated “soft separatism”, calling for dialogue with separatists, militants, and Pakistan, while demanding a high degree of autonomy for J&K. At its zenith, the PDP reshaped the political landscape of the Valley, posing a major threat not just to the NC but also to separatist factions in politics.

However, the party made a contentious decision in 2014 that continues to haunt it. After winning 28 seats in the Assembly elections, its best performance since 1999, the PDP formed a government by allying with the BJP. This marked the first time in the history of J&K that the BJP had risen to power at the state level. As predicted, the alliance was short-lived. In June 2018, the BJP withdrew its support, forcing Mufti to resign from the post of chief minister.

Indeed, all the regional forces have, at one time or another, taken an anti-Delhi stance to muster support from the public and have ultimately fallen in the lap of Delhi.

Nausheen, 37, a homemaker with a master's degree in Urdu, vents her frustration with Kashmir's politicians. “I feel humiliated by their tactics,” she says, sitting in a cosy corner of her home, surrounded by local newspapers scattered across a vibrant red Kashmiri carpet. “They’re all anti-Delhi before elections, only to work with Delhi after elections. We need real leaders, not reactionaries and opportunists who keep playing with our sentiments,” she says.

She adds: “It’s unfortunate that we have to choose from a crowd of pretenders, where everyone’s identity is that they are not a BJP proxy,” she added. Many in the Valley would agree.

Many argue that the state understands the sentiment and that's why it has backed new ‘proxies’ with a hardened anti-Delhi narrative to undercut traditional regional parties. Such a perception is cemented about Engineer Rashid; that he has been given a green signal to trumpet the anti-Delhi narrative so that the NC and the PDP are reduced to the margins.

Amid so much uncertainty, only one thing is certain—the cat will be out of the bag on October 8, when the results of the Assembly elections are declared.

(This appeared in the print as 'Agent, Agent Everywhere')

- Previous Story

‘Staying Out Of Power Has Made Congress Desperate’: PM Modi Slams Rahul Over ‘Country On Fire’ Remark

‘Staying Out Of Power Has Made Congress Desperate’: PM Modi Slams Rahul Over ‘Country On Fire’ Remark - Next Story