The Palladium cinema in the middle of Lal Chowk is half-burnt. Some distance from the clock tower Lal Chowk, the about-to-crumble cinema building is encircled with concertina wire. In front of the building is a huge CRPF bunker housing the security personnel. Outside the coils of concertina wires, a contingent of CRPF personnel having the latest weaponry is keeping vigil on the road and everyone who walks there.

A 70-Year Association With Bollywood Didn't Help Kashmiri Regional Cinema To Grow

Long cinema history and close links with Bollywood didn’t in any way help Kashmiri regional cinema. In fact, there is no regional cinema in Kashmir barring three films

Pallidum Cinema is a witness to Kashmir's political and insurgent history.?

In 1947, when Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah formed a Kashmiri militia to challenge Pakistani tribesmen, they would carry out drills in front of the cinema building to mobilise people. In 1948 it was in front of this cinema hall that Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru made a pledge to Kashmiris of holding a plebiscite to determine the future of Kashmir once the situation returns to normalcy. There are pictures of Pandit Nehru and Sheikh Abdullah shaking hands in a rally in front of the Palladium.

Since all major political developments of Kashmir have taken place in and around the Palladium cinema, it didn’t escape violent developments that hit Jammu and Kashmir in the past 70 years. On June 13, 1957, a bomb explosion took place outside the Palladium cinema. The Palladium Cinema was closed down in 1989 after the eruption of militancy in Jammu and Kashmir. A year later in 1990, the cinema was gutted in a fire and it has also seen two fidayeen attacks. In 2017, the government intended to develop it as a heritage museum.

Historian Khalid Bashir says it started by the name of Kashmir Talkies in 1932 and later adopted the name the Palladium Cinema perhaps after the Palladium theatre of the St.Petersberg. It was the oldest movie hall in north India and would screen Hollywood movies before these were released in Delhi which did not have a good market for English films then.

It is near the Palladium cinema Prithviraj Kapoor would stage plays including Yahudi Ki Ladki (The Daughter of a Jew), by an eminent Urdu poet, playwright, and dramatist Agha Hashar Kashmiri (April 1879–April 1935) in Lal Chowk, Srinagar.

But long cinema history and close links with Bollywood didn’t in any way help Kashmiri regional cinema. In fact, there was no regional cinema in Kashmir barring three films.

In Bollywood’s cinematic history, Kashmir’s Dal Lake, its rivers, mountains, snow slopes of Gulmarg majestic chinars, women peeping through windows looking at sheep herd, and beautiful children in dirty pherans have a special place. This imagery of Kashmir in Bollywood has so much impact on people that many outsiders get surprised to see Kashmiris who are not sheepherders or into shikara rowing.?

While the Valley’s scenic rendezvous with Bollywood took off with Raj Kapoor's Barsaat in 1949, gradually Kashmir’s scenery assumed its place in the Bollywood prominently. At times Kashmiris also were given some representation in the films like Mehmdu (Mehmood) wearing a coat and having a topi on his head begging Gopal (Rajindra Kumar) in Arzoo of 1965 to stay in his boat Jannat (paradise).

Even though this docile Kashmiri was turned into a gun-wielding scheming terrorist or scheming for terrorists in Bollywood representation of Kashmir after 1989 when insurgency erupted at a large scale in J&K, the Valley’s connection with Bollywood has remained deep. At the same time, Kashmir didn’t see regional Kashmiri cinema growing in any way.

In 1964, the first Kashmiri language based film Mainz Raat (Mainz-Mehndi, Raat- night) was released. It was directed by Jagjiram Pal, who hailed from Punjab. What prompted Pal to make the Kashmiri language based film no one has a clear answer.

But the film is seen as path-breaking for those times. It is a love triangle set in the village showing a Muslim boy in love with a Muslim girl and the hurdles they face. It also shows Kashmiri Muslims and Pandit bonhomie. It has several romantic and sad Kashmiri songs set in different seasons of Kashmir. The hero of the film was Omkar Nath Aima. His name in the film was Sulla. The film is remembered for folk songs and new Kashmiri songs, some of which were written by famous poet-writer-painter artist Ghulam Rasool Santosh.

Eight years later in 1972, another film was released and it was on poet Mahjoor. The film’s name was Shayar-e-Kashmir Mahjoor, a biography of Kashmiri poet Mahjoor. It was made in Urdu and Kashmiri. The film was a joint venture of the Department of Information of Jammu and Kashmir and Indian filmmaker Prabhat Mukherjee. Balraj Sahni acted as Mahjoor’s father, while Parikshit Sahni acted as Mahjoor. Parikshit Sahni once narrated that while travelling in Kashmir Balraj Sahni heard a boy singing a Kashmiri song. Since he did not know Kashmiri much, he asked for its translation. Sahni was impressed with the lyrics and their meaning. And he went on to meet Mahjoor. Both became friends. After the death of Mahjoor, he decided to make a film about him as a tribute to his friend. Parikshit Sahni says that had Balraj Sahni himself acted as Mahjoor in the film, it would have been a great hit.

The last regional Kashmiri language feature film was Inqilab (the revolution), says former director Doordarshan, Shabir Mujahid. The shooting of Inqilab started in 1989 in Pahalgam. Then the tumultuous events of 1989 didn’t prove good for the film as it was not released anywhere. Mujahid says the film was about a horseman in high mountains, his life, his love and his desires, and his struggle against landlords. Dipak Kanwal was its director and its whole cast was local.

Since then the digital platforms and streaming services that deliver content on the internet provided a new lease to regional cinema. This provided the regional language content with an audience beyond Kashmir. But it also didn’t much difference from Kashmiri cinema.

Ayash Arif, Kashmir’s top actor artist, argues that are many reasons that regional cinema didn’t grow in Kashmir and one of the reasons is a limited audience. He says the Kashmiri language cinema audience was limited to Kashmiris and Dogri language cinema was limited to only Dogri speaking audience thus complicating problems for the film-maker. However, the OTT platforms have to a large extent resolved the issue of an audience. He says the government must come up with a regional film finance corporation. “It is here regional local filmmakers submit their proposals and also get finances to make films. For regional cinema local producers should be given subsidies to help the regional cinema to grow,” says Arif.

Many, however, see Arshad Mushtaq’s Akh daleel loolech?(Akh-one, Daleel-story, Loolech-love), as the last regional ?Kashmiri language film. It is 100 minutes long. The story is about the 19th century (1887 to be precise) Kashmir when oppressive Dogra rulers would take people to bonded labour locally called 'begaar'. Mushtaq says he made the feature film in 2005 and it was well-received. ?He says except for a few well-known faces from TV, all the actors are new including the lead pair. Most of the performers are mainly from small theatre groups from across the length and breadth of the valley. ?“'Akh daleel loolech' is a small attempt to grab the attention of the people instigating the brains in this field of art to come up with many more such ventures to fill the void where there are no artistic impressions burnt on a film roll,” he adds.

After the abrogation of Article 370 and the downgraded of Jammu and Kashmir into Union Territory on August 5, 2019, the government has come up with a film policy. But the artists and filmmakers in the Valley call the policy more of a tourism promotion policy rather than a film policy as they allege the focus of the policy is attracting Bollywood to select Kashmir as a film destination but not promote regional cinema.

In its latest statement about the policy, the government on May 24 said, “Much to the benefit of the economy, Bollywood is again turning its eyes and cameras towards its once favourite shooting destination ‘Kashmir’ following the launch of Film Policy in Jammu and Kashmir,” ?thus proving the point of its critics.

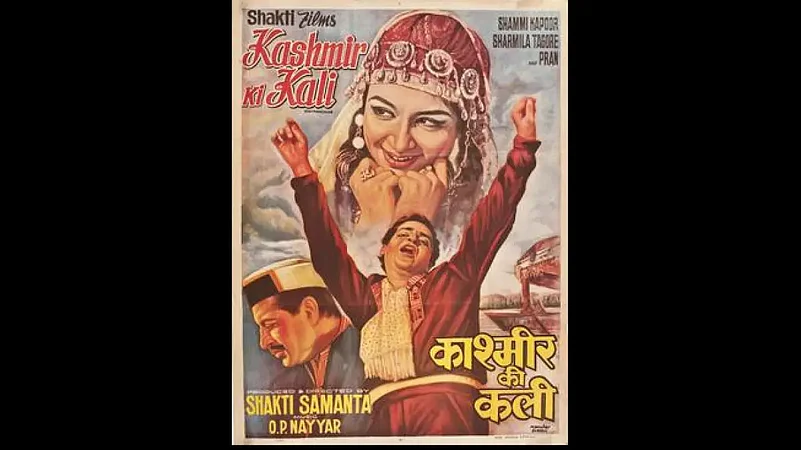

“Like the increase in footfall of tourists, film crews are also returning to Valley to capture the picturesque, shooting friendly locales which will give a huge fillip to Kashmir economy besides giving new dimensions to Film tourism,” an official statement said. “The residents in the valley are excited over the return of Bollywood which in its heydays during the '70s and '80 saw several mega-hits like 'Kashmir Ki Kali', 'Kabhi Kabhi' being shot in the exotic locations of the valley,” reads the official statement about the film policy.

Mushtaq says cinema has never found its roots in Kashmir when it comes to the language cinema, which would have been indigenous and mirroring the society. “The need is felt for the initiative and this medium can have a positive role to generate it. ?We might have missed the bus when the art of cinema began elsewhere, but it is never too late for us to make a beginning now. The non-existence of cinematic art or films in Kashmir does not mean that it should not be tried,” says Mushtaq.

Mushtaq says Kashmiris themselves have to tell their stories and cinema is the greatest medium. “We have great stories here. These are stories of Kashmir and they are about Kashmir. We should look toward Iranian cinema. We can also produce films of critical acclaim. Only if new and old filmmakers in Kashmir think differently,” he adds.