China-Plus-One. This is the new strategy being pursued by countries and companies, policy-makers and entrepreneurs, to survive in the re-imagined, re-aligned post-COVID world. Nations went through near-death experiences as they were economically strangled by the closure of China, the ‘Factory to the World’, and global supplier of most goods. As governments struggled to catch their breaths, given the manufacturing churn and choked throats, they witnessed the decimation of their globalised production models.

Mission Impossible? As Global Supply Chains Lie In Tatters, India Aims To Replace China As 'Factory To The World'

PM Narendra Modi is hoping to garner a whopping $330 billion by wooing foreign investors to 'Make in India'. The 'Buy Local, Be Global' mantra is also aimed at being self-reliant.

The destruction, not just of a well-oiled and seamless global supply chain, but also of a mindset, led to the concept of China-Plus-One. No one wants to put their eggs in a single manufacturing basket; no one wants to depend on a single source for their needs. Hence, there is a mad scramble to spread out, to seek out alternate suppliers. China may yet remain the No. 1 or No. 2 vendor for most nations, but it will not be the only one, not even a major one. This has presented an unprecedented opportunity to India.

India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi sensed that this could be the moment of a lifetime, a time to catch the bull by its horns. He realised that if he played the cards right–and he had a couple of aces up his sleeves–India could emerge as the new global manufacturing hub, a preferred destination for foreign investments over the next few years. He unleashed a slew of reforms, pushed states to enact controversial changes in laws, and re-wooed foreign investors to ‘Make in India’ in a bid to ‘Re-Make India’. Modi hopes to garner a whopping Rs 2,500,000 crore ($330 billion) in the next few years.

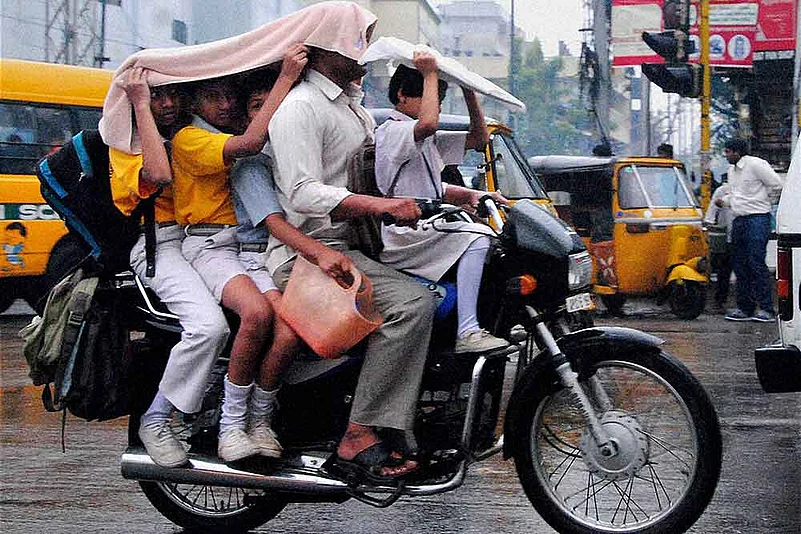

With its millions-strong young population, India has a demographic advantage over China

His new magic mantra to achieve this target is ‘Buy Local, Be Global’. It marks a combination of Swadeshi and 21st century globalisation, a modern version of ‘self-reliance’, a phrase that he mentioned 17 times in his 33-minute address to the nation on May 12. The initial aim is to cajole Indians to buy Indian products that are made not just by Indians but also foreigners. The overriding desire is to build a foundation that can catapult Indian exports, and enable India to become China 2.0, a global substitute for Chinese goods.

Santosh Pai, honorary fellow, Institute of Chinese Studies, dubs it as ‘Make in India 2.0’. He agrees that the trick is to make Indian firms competitive, and attract foreign capital for “true realisation of self-reliance”. Amitabh Kant, CEO, NITI Aayog, the Centre’s think-tank, views this as the initiatives to improve capabilities, scale up technologies, and diversify into new sunrise areas. “India has the respect and global appeal to attract investment. Luckily, the leadership is also building up the brand for India,” feels Harjinder Kaur Talwar, past president, FICCI FLO, the women’s wing of the industry association.

The FDI race is on

In the past three decades, ever since India embarked on the reforms journey in 1991, it has tried to hop on to the speeding global manufacturing bus. It didn’t succeed. One of the reasons was the country’s federal governance structure, compared to China’s single-party political system that doesn’t allow dissent. Hence, a foreign investor in a Chinese province or even a small city is treated like a royal guest. The red carpet is laid out, and the project is on stream with minimal delays and no cost overruns.

In contrast, thousands of Indian projects are either blocked or delayed by bureaucratic booby-traps, environmental activism, media criticism, scandals, and centre-state dissonances. To avoid some of these obstacles, the Modi regime has adopted a four-pronged plan this time. One, according to media reports, the Centre contacted more than 1,000 MNCs, which have manufacturing units in China, and wish to relocate them. The idea is to lure them with incentives, and convince them of India’s seriousness.

At the same time, Modi asked the various chief ministers to prepare actionable blueprints to attract foreigners, who seek new investment options. States such as Tamil Nadu, Punjab, and Rajasthan contacted key investors from countries such as Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, Japan, and the US, either directly or through their ambassadors. According to media reports, Amarinder Singh, the Punjab chief minister, said that he would provide the best support, infrastructure, and facilities to prospective investors. FICCI FLO’s Talwar agrees that Centre has to give more freedom to the states.

Both the Centre and states hope to expand the list of incentives, and opt for more reforms in a bid to charm the global billionaires. For example, NITI Aayog mooted a proposal to grant a four-year tax holiday to any investor, who wishes to bring in above $100 million. The period can be extended to 10 years for projects in labour-intensive sectors, reveal government sources. Apart from the past hikes in FDI limits in select sectors, a single-window Centre-state clearance system may be introduced in the near future.

A child with an oversized umbrella rides an ingenious bicycle sidecar

Finally, bilateral ties will be leveraged to push investment inflows. Take the case of Japan, which announced a fund of $2.2 billion to help its firms to quit China and relocate elsewhere. The idea is to diversify supply chain risk, and “re-shoring of strategically indispensable production”. Historically, India has had strong economic ties with Japan, and the ongoing ‘bullet train’ project is a notable example. Thus, New Delhi hopes to convince Tokyo to use a part of the fund to enable Japanese firms to expand in India.

The business tides are changing direction. In the past couple of weeks, there are reports that tech giant Apple may shift a fifth of its production capacity from China to India. CasaEverz, a German footwear company with 100 million global customers, plans to shift its entire production from China to Agra (Uttar Pradesh). Lava, an Indian mobile handset maker, has indicated that it too will shift its operations. The Red Dragon is under fire. The elephant is on the run. The race to grab billions of dollars of foreign money is on.

The ‘ILL’ effects

Pankaj M Munjal, CMD, Hero Cycles, says, “India is not a manufacturing country. For it to become one requires a mindset change. Our policies have not encouraged manufacturing in a big way.” Adds Pronab Sen, programme director, IGC India Programme, “Companies don’t care about statements of intent as they want to see evidence on the ground.” The three huge and recurring bottlenecks are the ‘ILL’ factors—lack of Infrastructure, issues in Land acquisition, and inflexible Labour laws.

One of the planks of China’s economic success rests on its industrial clusters, special economic zones (SEZs), and the concept of one-town one-product. They allow the country to offer “integrated infrastructure” to companies, which can source all their requirements—a long laundry list—from the same place. The SEZs include elaborate additional facilities such as centres of invention, incubation, testing, trade facilitation, foreign transactions, and official approvals of standards and quality.

A Chinese girl looks on from behind the glass frontage of a shop

After past failures, India hopes to re-construct similar clusters and SEZs. “We can expect a change in the policy approach towards SEZs. The government may develop one huge area as an industrial hub. This will attract companies trying to trans-locate from China, South Korea, and Japan,” feels Sachin Chaurvedi, director-general, Research and Information System for Developing Countries. A key theme of such industrial estates may be the “plug-and-play” model to allow investors to “hit the ground running”.

To tackle delays in land acquisition, India has identified 461,589 hectares of land—almost double the size of the country of Luxembourg—to prepare a land pool bank. It includes new areas, and 1,15,131 hectares of existing industrial land in states such as Gujarat, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh, which are favoured by investors. Using technology, companies can pinpoint and select the land that fulfils their needs. This will hasten project implementation in a big way.

Another way to avoid time and cost overruns is to hand over readymade projects on a platter to willing investors. To cite an example, the state-owned BHEL has offered partnerships to foreign firms to use its idle and additional capacities at its 16 manufacturing units across the country. This implies that BHEL’s licences, operational factories, skilled workforce, and additional land is immediately available for expansion. Other PSUs, many of which have spare capacities, may soon ink similar agreements.

Graphics by Saji C.S.

For years, experts cited India’s strict labour laws, which tied the hands of the employers who were unable to hire-and-fire workers, as a major reason for the apathy among MNCs to aggressively invest in India. Most Indian regimes were scared of the political and electoral backlash if they tinkered with them. In the post-COVID environment, several states have changed labour laws. Some like Uttar Pradesh banned most of the acts related to workers. This, feels its chief minister Yogi Adityanath, will entice foreigners.

Despite such measures, transforming India into a global hub may prove to be a Herculean task. India’s past efforts to build SEZs were a mix of partial successes and failures. Six years ago, Gujarat asked a Chinese firm to build an industrial park. Although the firm acquired 200 acres, construction hasn’t started. Flexible labour laws that neglect workers’ conditions, factory environment, and safety may dissuade foreigners, who are bound by stricter codes of their respective countries and corporate headquarters.

Competition is intense

India isn’t the only one trying to initiate a new love affair with MNCs. There are others—Korea, Taiwan, Vietnam, Thailand, and, of course, China. Beijing is on the back foot because of the manner in which it handled the COVID crisis initially, and the manufacturing mayhem due to the closure of its factories. It has now gone on the offensive to prove its worth. The fact remains that no other nation has the manufacturing ecosystem that China has. “I don’t think there will be a major investment outgo from China,” says Mohammed Saqib, secretary-general, India China Economic and Cultural Council.

Tall residential towers reflect on the chrome facade of a building

Vietnam, Korea, Thailand and Taiwan may be better placed to woo investments, if recent experiences are any indication. According to a study by Nomura, a Japanese financial group, 56 companies relocated their production bases from China during the height of its trade wars with the US in 2018-19. Of these, 26 went to Vietnam, 11 to Taiwan, and eight to Thailand. Only three came to India. Similarly, since June 2018, the US imports from Vietnam “soared by more than 50 per cent and those from Taiwan by 30 per cent”.

One of the reasons is that these Asian nations have closer economic and cultural ties with China. Even if the foreign entities wish to move out of China, they want to remain closer to its borders. The reason, explained Parag Khanna, the author of The Future is Asian, in a recent interview is because of the new pressures due to “regional integration”, as opposed to globalisation. Global trade today follows the dictum of “sell where you make”, and companies hope to “near-source” their production; that is, remain closer to the consumption centres rather than “outsource” it to far-flung territories.

Given this mindset, despite the ‘China distrust’, foreign MNCs may wish to relocate in the vicinity of China to take advantage of the booming Asian demand and huge domestic consumption. The more than a dozen free trade agreements (FTAs) that China has signed with Asian nations help. These FTAs ensure that the duties on exports from Vietnam, Taiwan, and Korea to China are either zero or minimal. Hence, the trade routes remain open.

India too has signed major FTAs with ASEAN, Korea, and Japan. However, these haven’t worked the way they should have. In the past decade, the annual trade balances in the three cases were against India; that is, India imported way more from them compared to its exports. For example, the annual trade deficit with ASEAN almost trebled to $22 billion in 2018-19. This needs to change if India has to establish itself as a global supplier of goods.

Fortunately, there is good news. Compared to FDI competitors like Vietnam at least, India is better placed. Although Vietnam is the largest gainer of FDI in recent times, this doesn’t give it a special edge over India. Vietnam attracted just over $38 billion foreign investment in 2019, which was lower than India’s $49 billion. Like China, India’s vast local market is an incentive for potential investors to pursue their local-regional-global strategies. Let’s not forget that India is the eighth most important FDI destination in the world.

Research edge

No country can become the vendor to the world unless its producers are backed by the government, it has quality infrastructure and its labour laws are flexible. What is crucial, and most people forget this, is a sturdy, innovative, and vibrant R&D setup. “China’s manufacturing strength in key supply chain items such as chipsets, sensors, and transponders does not rely on cheap labour, but instead on indigenous intelligent properties,” explains Dev Lewis, Yenching Scholar, Peking University.

Chinese universities played a pivotal role to not just invent new technologies and engage in fresh discoveries, but also to incubate and launch start-ups that possess new knowledge and processes. Coordinated research between academia and business ensures constant forays in garnering new patents and intellectual properties. Technology cannot be developed under a single shed; it requires active collaboration between the various stakeholders.

Sadly, India has failed on this front. Although it is a leader in secondary research—the ability to do reverse engineering in pharmaceuticals, for example—it has lagged in new inventions. A long-term vision is required. R&D has to emerge as an important plank for India to become an innovator, rather than a mere supplier. More importantly, advancements in technology will lead to lower costs, higher skilled employment, and enhancement in the manufacture of quality products.

In the final analysis, India has made a good beginning in its attempt to wrest the manufacturing crown from China. But it is still an uphill task. India has the intent, talent, and capabilities. What it needs is a five-year comprehensive and detailed strategy blueprint, which is developed after a close study of the strengths and weaknesses of countries like China and Vietnam. In the past, Indian policy makers and businesses were either risk averse or saddled with doubts and lack of ambition. This time around, Modi hopes to bridge this mindset gap with the national call for self-reliance. Yet again, the global manufacturing bus has halted for India. It needs to jump on it sooner than later. We cannot afford to miss this journey.

Vox PoP

Harjinder Kaur Talwar

FICCI FLO’s Past President

India needs to upgrade. It does not matter where we stand today in context of China. What matters is where we want to see ourselves. We have to be competitive in manufacturing capabilities and cost. India has respect and global appeal to attract the investments. Luckily, the leadership is building up a brand for India. At this point if the Industry does not grab and upgrade itself technically and in quality to compete, we will lose this opportunity. India is flexible in terms of global relationships. Quality is the key to ensure FDI and Indian units must focus on it. We need improvement in infrastructure sector, more freedom to states by the Centre, and quality adherence.

Mike Chen

General Manager, TCL India

India has many appeals-—it is one of the fastest-growing economies, and projected to maintain this position despite the unc-ertainty caused by COVID-19. It offers impressive growth opportunities, and larger investment ret-urns in the long term. Initiatives like ‘Make in India’ and ‘Digital India’ are growth drivers. Localisation is a key to success. Investors have put in around Rs 300 billion in Tirupati’s electronics hardware sector. It can become the silicon corridor of India. India can become a global manufacturing hub if it goes with the same pace and scale. We sensed India’s potential a few years ago, and set up a Rs 2,400 crore-unit in Tirupati. It is our largest manufacturing facility outside China.

Also Read

—with inputs by Lola Nayar