SCENE 5: NOTHING

Tracing Occupation Stories In Palestine

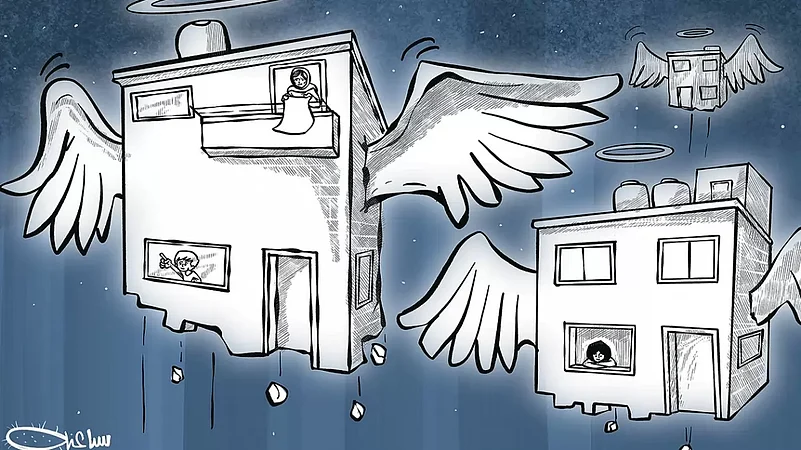

A collection of plays by Palestinian theatre groups about the daily lives of people in wartime in their ‘homeland’

I had some things. Where are they? Where are my things? Where are they? Where are my things? Ah, I had . . . I had some books. I took the books. I had four books. I took four books from our home. Our home?

Oh, yes, our home . . . !

(She imagines her home.)

Our home had a blue gate, stairs and handrail, I used to go up the stairs. Hey . . . no! Our home was on the first floor. I used to go out of my room straight to the garden. I remember the dog that I used to play with. I used to pet it with these hands. These are not my hands. My hands were full. They were full with gold and bracelets. My father bought me a ring.

(Looks for her father.)

My father! My father! My father! I used to sit in his lap and play with his mustache. He had such a moustache. I can’t remember how my father looked. I can’t remember? How did this happen to me? How did I lose all those things? What does this mean? I’m not me anymore! Did I disappear? I’m nobody . . . I . . . I’m nothing, a persona non-grata. I am less than an unknown. I am nothing.

SCENE 7: SUITCASE AND CHECKPOINTS

ISMAIL. You should be proud that you are carrying the most important thing in my life. You are carrying the smell of my homeland, my village, the dreams of my people, their pains, struggles, longings, exile, and tears. Tomorrow, you will see when we return to the village. You’ll see how beautiful life is there. You’ll be euphoric. All the people will welcome you at the entrance of the village. They’ll say: This is the most important suitcase in the world. The most important suitcase!

SCENE 12: KING SOLOMON

KAMEL. A satirical writer said to me once, “If I knew the end from the beginning, I wouldn’t have use for language.” Everyone makes fun of me. They all tease me. All your stories are about heroes, you don’t have stories about the woman who stays at home with her kids . . . about the teacher who teaches the students in school . . . about the peasant who plants his land . . . about the worker in the factory. You are driving me crazy, you are making fun of me.

We Are The Children of the Camp

ALL. Twelve camps in Lebanon, ten camps in Jordan, ten camps in Syria,

and others and others

(They sing.)

We are the children of the camp

We are the sons of refuge

We are the children of exile

We are the lovers of resistance

We have been chased from our homes

Our lands were taken

We were forced to live in tents

We became refugees

They uprooted the olive trees

They constructed colonies

They thought that we have no history

Or thought that we didn’t exist

They demolished all of our villages

They put us in labyrinths

They planted hatred in us

They considered us as insects

We may have a spring

Sun may rise again in our sky

We look to Jerusalem

Singing for freedom in our hearts

We will never forget

We will never forget

We will never forget

We will never forget

Blackout.

The Gaza Monologues

AHMAD EL RUZZI

Born 1993

Al Wehda Street

Before the war, I used to feel that Gaza was my second mother. Its? ground was the warm chest I could lay on, and its sky was my dreams . . .without limits. The sea would wash away my worries. But today I feel it’s an exile, I stopped feeling it’s the city of my dreams. In the war, the main electricity pole was hit by a huge rocket. All my uncles were at home with us and the electricity went out, but there was another line working, near to the house. I went to our neighbor and asked him for an extension so we could connect to the second line. Once we were connected, and our house was lit, he came to take the extension back. We had a huge fight.

In war, everyone thinks about themselves. During the war, a lot of people had twenty bags of flour and never had a shortage of gas, while others didn’t have a piece of bread . . . they were asking their neighbors for bread and they wouldn’t give them any. Most people locked up their things under lock and key and decided not to give anything to anyone. But others were good and helpful. Back to our topic: we didn’t agree to return the connection to him even though it was his extension that we were using, and for the first time I realized how bad we can be. We were punished on the spot. The house next to ours was bombed and split in two pieces, and half of it fell on us. We left the connection and electricity and everything and ran away to my uncle’s house next to the municipal park.

My uncle’s house is close to a government building, and in the evening people started saying that building would be bombed, and if it was bombed, my uncle’s house might disappear from existence! We sat there not knowing what to do or where to go. My dad kept reassuring us: “Don’t worry, don’t be scared, nothing will happen.” We stayed like that till midnight. We kept hearing rockets and explosions, and my dad kept saying, “don’t worry and don’t be scared,” but suddenly he said: “Follow me! We’re going back home!” And he started shaking. All of us started shaking with him. My mum started screaming and my uncle was in really bad shape. Anyway, all of us ran away in the middle of the night with my uncle’s family.

We ran home . . . couldn’t believe it when we got home. Till today I don’t remember where we slept or how. The important thing was that we were away from that building. We found that our neighbor had taken the electricity connection, and we spent the night in darkness while his house was lit. I felt he was right to take his connection back.

After that my dad got a connection complex . . . he bought 3 electric cables and 6 gas bottles, 2 electric pans, 20 neon lights, 20 packs of candles, 6 packs of cans, 10 packs of wires, 6 flashlights and 2 boxes of batteries. We’re living in war and we have to be careful till things get better. I got a complex worse than all others. It’s as though I was generous before the war, or maybe I didn’t know the value of things, because I couldn’t believe that there would be a day when I wouldn’t find a drink of water or a piece of bread. But after the war I became super careful with everything and anything; I started barely sweetening my tea. And if I broke a loaf of bread, I wasn’t allowed to finish it. I lost my appetite for food and became really economical. My dad says: “Ahmad always has his pocket money”. . . Of course, because I take it and save it in case there’s another war! I feel like I’m married with ten kids. I’m scared of life . . . of everything . . . of the smallest things . . . always worried. I feel that all of Gaza is sitting on moving sands. Any madness you can imagine can happen in a second in this place, and a lot of dreams may come true too. It’s a strange city with no logic. China is now a third of the world, and they all work but can barely make enough shoes and shirts for Gaza. Gaza consumes everything, and the world attacks it, but it keeps pretending nothing is wrong.

(Excerpted from Stories Under Occupation and Other Plays From Palestine, Edited by Samer Al-Saber & Gary M. English,? with permission from Seagull Books)

(This appeared in the print as 'Occupation Stories')