Mohammad Hassan was “shot” outside the Shahi Jama Masjid in Sambhal, in northern Uttar Pradesh, on the morning of November 24. He still doesn’t fully understand how it happened.

In Sambhal, An Engineered Silence

It weighs heavily on the stillness of the empty streets in the centuries-old town of Sambhal, Uttar Pradesh, where clashes with police over yet another ‘mandir-masjid’ dispute led to the deaths of local Muslim men

Hassan had gone searching for his younger brother amidst the pathraaw (stone pelting) outside the mosque, when either a bullet or shrapnel pierced his body, injuring his right arm. He didn’t see which “side” the projectile came from—locals or the police—and didn’t notice who was firing what.

“Main beech mein phans gaya. Jo bhi tha, aar paar chala gaya,” (I got stuck in the middle. Whatever it was, it went through me) he said three days later at the Sambhal district hospital, where policemen brought him after first taking him to the kotwali.

He is one of 2,500 people—many of whom are unidentified—booked by the Sambhal Police for Sunday’s violence, which left five dead. Locals and leaders allege police fired fatal shots during clashes over a court-ordered “survey” of Sambhal’s Shahi Jama Masjid, following claims that the mosque was built on temple ruins.

Hassan’s sister, Ashiya Bibi, said her brother told her he had been “shot with a bullet” and is “in custody” for suspected involvement in the violence. She also mentioned that the family is under immense pressure. “Hassan wasn’t part of the crowd. He had just gone to look for our younger brother. Our father died only 20 days ago and we later found out the younger brother had gone to offer prayers at his grave nearby,” she said. “Hassan was in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

There are others in Sambhal who echo her travail, namely the families of five men, all working-class Muslims, including two teenagers, who died in the Sunday violence.

Mohammad Ayaan, 17, was heading to the eatery where he worked. Mohd Kaif, 18, sold cosmetics and was out buying materials for his stall. Bilal Ansari, 22, a handloom shop owner, awaited a delivery after securing a major deal with a Delhi distributor. Nayeem Ghazi, 35, ran a sweet shop and left home to purchase oil and flour. All lost their lives in the violence that erupted, leaving their families devastated.

Locals and eyewitnesses say tensions had been high in Sambhal’s Muslim-majority neighbourhoods since Tuesday, November 19, when a group of Hindu petitioners, including advocate Vishnu Kumar Jain, filed a petition in the District and Sessions Court of Civil Judge Aditya Singh. The petition claimed the mosque was built on the ruins of the Hari Har Temple and sought to determine the site’s character, demanding it be opened for Hindu worship. Incidentally, Jain has been involved in similar lawsuits in Ayodhya, Varanasi and Mathura.

Old Petition, New Ink

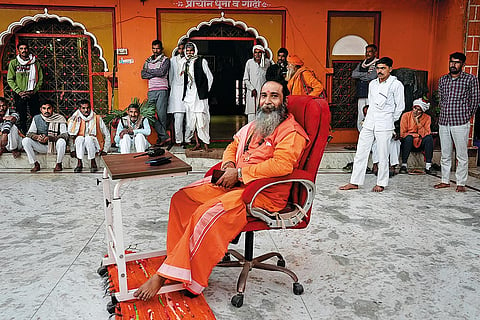

About 20 km from the mosque, Mahant Rishiraj Giri, head priest of the Kaila Devi temple in Sambhal and one of the Hindu petitioners, has spent the past week giving interviews, claiming it was “Hari” (God) himself who instructed him to file the petition to reclaim the mosque.

“It is the Hari Har temple. It has always been. Babur destroyed the temple to build a mosque,” he asserts, speaking between the crackling static of his walkie-talkie, in the presence of armed police personnel. He cites these as “facts” documented in texts like Baburnama and Ain-i-Akbari. “It’s all in the petition. It’s also on the internet,” he insists.

He says what happened on Sunday should not have occurred. “The deaths are unfortunate. However, locals should not have interfered with the court-ordered survey work,” he said. He claimed there was “intricate Hindu temple architecture inside the mosque compound”, but admitted he had never entered the mosque. While he described seeing the Hari Har temple in Sambhal as his “childhood dream”, he also said he decided to file the petition only in the “last year or two”.

But Why Now?

The Kaila Devi priest claims the petition was filed now, after centuries of the mosque’s existence, because “God willed it”. However, the Muslim side alleges that the decision to conduct the survey was “hasty” and disregarded the potential for communal unrest.

“The survey order was passed on November 19 within hours of the petition being filed. The survey began at 5:30 pm without proper notices issued to the administration or the mosque committee, as is standard in such cases,” said Qamar Hussain, a Sambhal-based advocate and part of the mosque’s legal counsel team. He joked that the petition is “old wine in a new bottle,” adding, “Since the Ayodhya judgement, it seems to have become a trend to target Muslim places of worship.”

Mandir-masjid controversies have become a staple of Indian political discourse, often following a familiar script. In Varanasi (2022), the Gyanvapi mosque dispute escalated after a court-ordered survey claimed the mosque was built on Shringar Gauri temple ruins, leading to the alleged discovery of a Shivling. Similarly, in Mathura, Hindus claim the Shahi Eidgah mosque is built on temple land and marks Lord Krishna’s birthplace, sparking demands for worship rights within these structures.

Less known than Ayodhya, Kashi or Mathura, Sambhal’s mosque has long been a point of communal contention. In 1976, its imam (prayer leader) was murdered inside the premises by a Hindu fanatic on Shivratri, triggering month-long curfews and tensions. Cleric Mamluk Ur Rahman Barq recalls the incident’s lasting impact. Now, his son, Samajwadi Party MP Zia-ur-Rehman Barq and MLA Nawaz Iqbal Mehmood’s son, Sohail Iqbal, face police charges for allegedly instigating the violence. Sambhal SP Krishna Kumar Vishnoi alleges tensions escalated after Barq made inflammatory remarks about preserving the mosque, worsening the volatile situation.

Barq senior and local SP leaders believe there are other political motives at play. “The Kundarki by-elections were held a day after the first survey, possibly aimed at fomenting communal trouble. The BJP won Kundarki after 30 years and the next day, another survey took place, likely to intentionally provoke the minority population here,” he said.

The BJP has accused the Samajwadi Party of inciting violence. On Monday, Uttar Pradesh Excise Minister Nitin Aggarwal blamed the “arson and violence” on a power struggle between the Turk and Pathan communities.

Barq, of Turk origin, was accused of sparking tensions with Pathan community leader Sohail Iqbal. Barq, the former Kundarki MLA, whose Lok Sabha 2024 win led to the recent Kundarki by-poll, is attending Parliament’s Winter Session in Delhi. He claimed the police named him in the FIR to “hide the truth”, speaking to reporters outside Parliament.

History of Contention

Claims that the mosque was built on temple land trace back to a 19th-century report by British archaeologist A. C. L. Carlleyle. The 1979 Archaeological Survey of India report, cited by present petitioners, noted the mosque was constructed with rubble masonry that could have been from a temple. It also questioned the authenticity of the inscription naming Babur as the mosque’s benefactor, casting doubt on his involvement in its construction.

Sambhal is believed to be the birthplace of Kalki, the 10th avatar of Vishnu, prophesied to end the ‘Kali Yug’ in Hindu mythology. The Jama Masjid is located about 200 meters from the ancient Kalki worship site, which the BJP government recently renovated. Prime Minister Narendra Modi visited the temple during its inauguration in February this year.

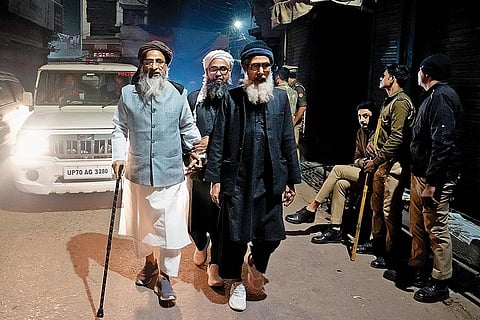

Jamiat-Ulama-i-Hind General Secretary Mohammad Hakimuddin Qasmi, who led a delegation to Sambhal after the incident, said the committee “had faith” in the country’s laws. “For centuries, we have prayed at this mosque and no one has had an issue. The Places of Worship Act, 1991, was intended to ensure communal safety and the integrity of places of worship, especially for minorities. We hope it will prevail,” he said.

The Sambhal Shahi Jama Masjid Committee has approached the Supreme Court and has sought a stay on the November 19 order.

Silence in Sambhal

Meanwhile, in Sambhal, an oddly engineered silence weighs down the stillness of the empty streets. Twenty-seven people have been arrested since the violence, all Muslim, including three women and three minors. Over 70 people have been detained, based on videos, drone images and other sources. Many doors, windows and shopfronts remain boarded up and young and middle-aged men are missing from localities, fearing arrests. Even the sobs of those who lost a family member in what all agree was “avoidable” violence are muffled, with families afraid to grieve aloud.

“Police have been raiding homes and harassing people, accusing them of firing,” said Nayeem Ghazi’s mother, Idrisa. Family members of Mohammad Kaif and Mohammad Ayan share similar woes. Kaif’s brother, Zaid, was picked up during a raid after Sunday’s violence and allegedly assaulted. It was only after the family pleaded with the cops, citing Kaif’s death, that Zaid was released. Mohammad Hussain, Kaif’s father, was unwilling to discuss the matter further. “We are poor people. We’ve already lost our young son. We don’t want any more trouble,” he said with folded hands.